Research

The 22nd Meeting: "The Intuition" of the Artificial Intelligence, Art, and Aesthetics Research Gruop (AIAARG). December 23, 2018.

The psychology of subliminal thoughts— An unknown “you” inside you?

In Edgar Allan Poe's The Imp of the Perverse, the protagonist follows self-destructive impulses arising from the temptation to do things merely because we feel we should not.

As we go about our daily lives, we might feel like we are in regular control over our consciousness. However, recent research indicates that our thoughts and actions are heavily influenced by mental processes that we are unaware of.

In this lab, we research this topic by conducting experiments in which we use hidden stimuli.

Related Papers

Hattori, M., Sloman, S. A., & Orita, R. (2013a). Effects of subliminal hints on insight problem solving.Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20(4), 790–797. doi:10.3758/s13423-013-0389-0

Hattori, M. (2014g). Subliminal problem solving: Dual processes of cognition and their interaction.The Second New Paradigm Psychology of Reasoning Conference. École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris, France. June 5.

Further Readings

Flashes of inspiration and creativity— Good ideas strike us suddenly?

Often, we rack our brains for ideas, but the good ideas just don't seem to come. But then, sometimes, when we are doing or thinking about something completely unrelated, a great or brilliant idea suddenly and inexplicably pops into our heads.

Where do these flashes of inspiration come from? Is it possible to improve creativity through willful efforts?

With a view to finding answers to these questions, we conduct experiments to unravel the mechanisms of insightful and creative thinking.

Related Papers

Hattori, M., & Yoshida, Y. (2000a). Creativity, implicit cognition, and meta-cognition. Proceedings of the 64th Annual Convention of the Japanese Psychological Association, 818. Kyoto University. (In Japanese)

Yoshida, Y., & Hattori, M. (2002a). Effects of metacognitive processing on creative problem solving. Cognitive Studies: Bulletin of the Japanese Cognitive Science Society, 9(1), 89–102. doi: 10.11225/jcss.9.89 (In Japanese with English abstract)

Yoshida, Y., Hattori, M., & Oda, M. (2005a). The relationship between idea search space and creativity. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 76(3), 211–218. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.76.211 (In Japanese with English abstract)

Causal reasoning and symmetry in reasoning— “It’s all your fault!”

When an incident such as a fire occurs, people speculate on what might have caused the incident. This kind of casual reasoning constitutes a cognitive activity that we naturally perform throughout our daily lives.

People might conclude that the cause of the fire was a burning cigarette, but why do they disregard the presence of oxygen as a causal factor? How does one determine the true cause of an incident from among an infinite number of possible causes?

We have a tendency to seek a singular cause for each event. Based on the assumption that this tendency is related to a range of seemingly unconnected cognitive biases, we conduct experiments aimed at uncovering these hidden connections.

Related Papers

Hattori, M., & Oaksford, M. (2007a). Adaptive non-interventional heuristics for covariation detection in causal induction: Model comparison and rational analysis. Cognitive Science, 31(5), 765–814. doi: 10.1080/03640210701530755

Hattori, M. (2008a). Symmetry in reasoning, and reasoning in symmetry. Gengo, 37(3), 4–5.(In Japanese)

Hattori, M. (2008b). The equiprobability hypothesis of reasoning and judgment: Symmetry in thinking and its adaptive implications. Cognitive Studies: Bulletin of the Japanese Cognitive Science Society, 15(3), 408–427. doi: 10.11225/jcss.15.408 (In Japanese with English abstract).

Further Readings

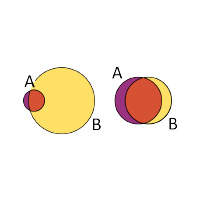

A probabilistic approach to logical reasoning— Though the reverse is not true…

The importance of logical thinking has been emphasized in education and business. Logical thinking is hard because our minds are geared toward thinking in terms of likelihood (probabilities).

For example, assume that your friend tells you that he will phone you if he passes his examination. If you subsequently receive a phone call from him, it does not necessarily mean that he has passed. “If A then B,” it does not necessarily imply that “B follows A.” However, you know that it is unlikely that your friend would ring you up when he has failed, and based on this knowledge, you infer that your friend has passed. Such an inference, though logically fallacious, might nevertheless be an advantageous line of reasoning, because there is a high probability that the inference is indeed accurate.

Thus, we use probability analysis to demonstrate how easy it is for us to commit logical fallacies.

Related Papers

Hattori, M. (2016c). Probabilistic representation in syllogistic reasoning: A theory to integrate mental models and heuristics. Cognition, 157, 296–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.09.009

Hattori, M. (2002d). A quantitative model of optimal data selection in Wason's selection task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Experimental Psychology A, 55(4), 1241–1272. doi:10.1080/02724980244000053

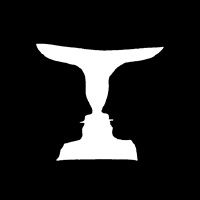

Rubin's (1921) vase

“Figure and ground” in thinking— Why is it so difficult to deduce the solution from “the dog that didn't bark”?

In “Silver Blaze,” one of Sherlock Holmes's short stories, the great detective identifies an important clue in “the curious incident of the dog in the night-time”; the fact that the dog did nothing in the night-time was the curious incident. However, humans are generally poor at noticing “non-occurring” things, like a dog not barking.

Logically speaking, occurrence and non-occurrence are akin to affirmation and negation, respectively. Psychologically, however, they are a kind of the “figure and ground” relationship, with occurrence being the figure and non-occurrence being the ground. In other words, when expressed in logic notation, affirmation and negation are symmetrical, but psychologically, they are asymmetrical.

Assuming that the asymmetry in our thinking as described above is a common factor underlying various cognitive errors and biases, we conduct various experiments aimed at verifying this assumption.

Related Papers

Hattori, M., Over, D., Hattori, I., Takahashi, T., & Baratgin, J. (2016a). Dual frames in causal reasoning and other types of thinking. In N. Galbraith, E. Lucas, & D. Over (Eds.), The thinking mind: A festschrift for Ken Manktelow (pp. 98–114). London: Routledge.

Hattori, M. (2014d). Figure and ground in thinking: The affirmation–negation asymmetry as a consequence of framing. The Ritsumeikan Bungaku: The Journal of Cultural Sciences, 636, 131–147. (In Japanese with English abstract)